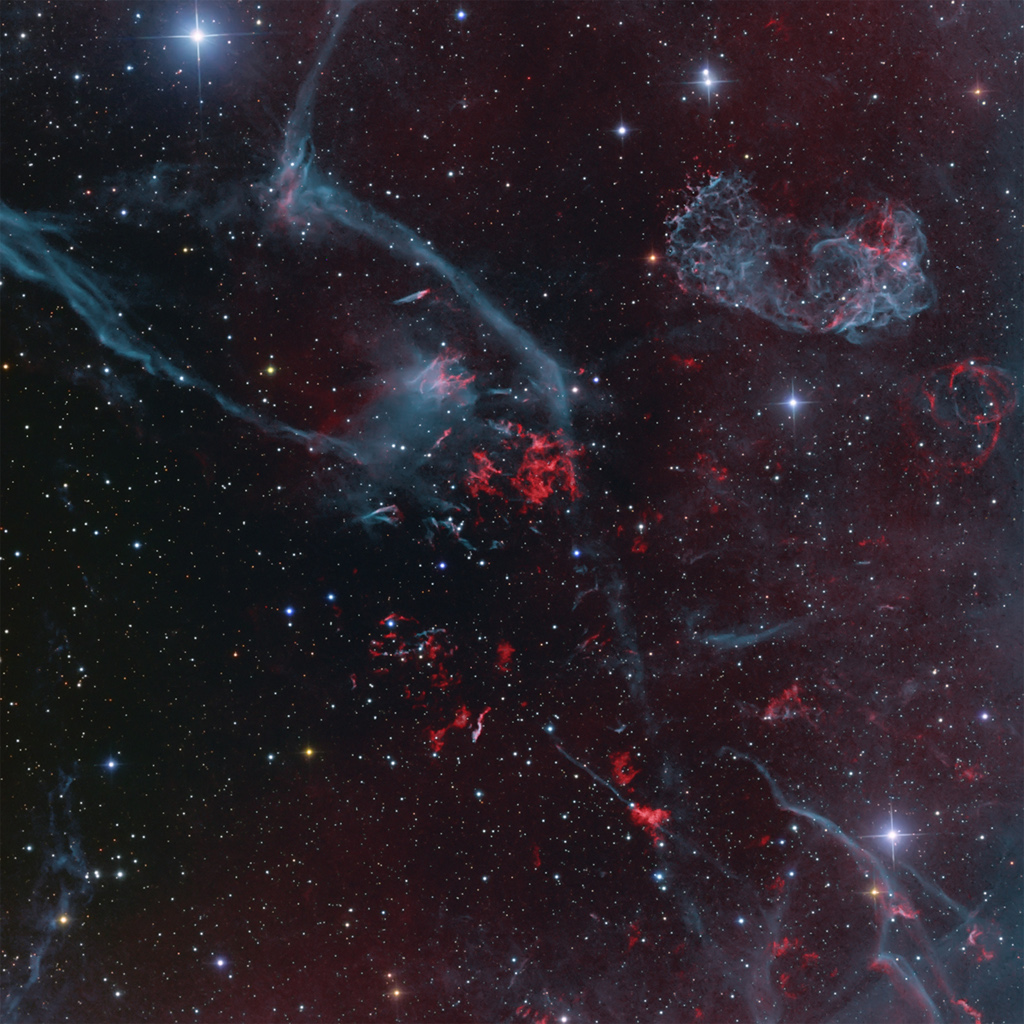

Look through the cosmic cloud cataloged as NGC 281 and you might miss the stars of open cluster IC 1590. Still, formed within the nebula that cluster's young, massive stars ultimately power the pervasive nebular glow. The eye-catching shapes looming in this portrait of NGC 281 are sculpted columns and dense dust globules seen in silhouette, eroded by intense, energetic winds and radiation from the hot cluster stars. If they survive long enough, the dusty structures could also be sites of future star formation. Playfully called the Pacman Nebula because of its overall shape, NGC 281 is about 10,000 light-years away in the constellation Cassiopeia. This sharp composite image was made through narrow-band filters, combining emission from the nebula's hydrogen, sulfur, and oxygen atoms in green, red, and blue hues. It spans over 80 light-years at the estimated distance of NGC 281.

Look through the cosmic cloud cataloged as NGC 281 and you might miss the stars of open cluster IC 1590. Still, formed within the nebula that cluster's young, massive stars ultimately power the pervasive nebular glow. The eye-catching shapes looming in this portrait of NGC 281 are sculpted columns and dense dust globules seen in silhouette, eroded by intense, energetic winds and radiation from the hot cluster stars. If they survive long enough, the dusty structures could also be sites of future star formation. Playfully called the Pacman Nebula because of its overall shape, NGC 281 is about 10,000 light-years away in the constellation Cassiopeia. This sharp composite image was made through narrow-band filters, combining emission from the nebula's hydrogen, sulfur, and oxygen atoms in green, red, and blue hues. It spans over 80 light-years at the estimated distance of NGC 281.Zazzle Space Gifts for young and old