By applying a new computational analysis to a galaxy magnified by a gravitational lens, astronomers have obtained images 10 times sharper than what Hubble could achieve on its own.

via Science Daily

Zazzle Space Exploration market place

There are advances being made almost daily in the disciplines required to make space and its contents accessible. This blog brings together a lot of that info, as it is reported, tracking the small steps into space that will make it just another place we carry out normal human economic, leisure and living activities.

Gravitational lens helps reveal "fireworks" in the early universe

When the universe was young, stars formed at a much higher rate than they do today. By peering across billions of light-years of space, Hubble can study this early era. But at such distances, galaxies shrink to smudges that hide key details. Astronomers have teased out those details in one distant galaxy by combining Hubble’s sharp vision with the natural magnifying power of a gravitational lens. The result is an image 10 times better than what Hubble could achieve on its own, showing dense clusters of brilliant, young stars that resemble cosmic fireworks.

Image representing the new particle observed by LHCb, containing two charm quarks and one up quark. (Image: Daniel Dominguez/CERN)

Today at the EPS Conference on High Energy Physics in Venice, the LHCb experiment at CERN’s Large Hadron Collider has reported the observation of Ξcc++(Xicc++) a new particle containing two charm quarks and one up quark. The existence of this particle from the baryon family was expected by current theories, but physicists have been looking for such baryons with two heavy quarks for many years. The mass of the newly identified particle is about 3621 MeV, which is almost four times heavier than the most familiar baryon, the proton, a property that arises from its doubly charmed quark content. It is the first time that such a particle has been unambiguously detected.

Nearly all the matter that we see around us is made of baryons, which are common particles composed of three quarks, the best-known being protons and neutrons. But there are six types of existing quarks, and theoretically many different potential combinations could form other kinds of baryons. Baryons so far observed are all made of, at most, one heavy quark.

“Finding a doubly heavy-quark baryon is of great interest as it will provide a unique tool to further probe quantum chromodynamics, the theory that describes the strong interaction, one of the four fundamental forces,” said Giovanni Passaleva, new Spokesperson of the LHCb collaboration. “Such particles will thus help us improve the predictive power of our theories.”

“In contrast to other baryons, in which the three quarks perform an elaborate dance around each other, a doubly heavy baryon is expected to act like a planetary system, where the two heavy quarks play the role of heavy stars orbiting one around the other, with the lighter quark orbiting around this binary system,” added Guy Wilkinson, former Spokesperson of the collaboration.

Measuring the properties of the

Ξcc++ will help to establish how a system of two heavy quarks and a light quark behaves. Important insights can be obtained by precisely measuring production and decay mechanisms, and the lifetime of this new particle.

The observation of this new baryon proved to be challenging and has been made possible owing to the high production rate of heavy quarks at the LHC and to the unique capabilities of the LHCb experiment, which can identify the decay products with excellent efficiency. The Ξcc++ baryon was identified via its decay into a Λc+ baryon and three lighter mesons K-, π+ and π+.

The observation of the Ξcc++ in LHCb raises the expectations to detect other representatives of the family of doubly-heavy baryons. They will now be searched for at the LHC.

This result is based on 13 TeV data recorded during run 2 at the Large Hadron Collider, and confirmed using 8 TeV data from run 1. The collaboration has submitted a paper reporting these findings to the journal Physical Review Letters.

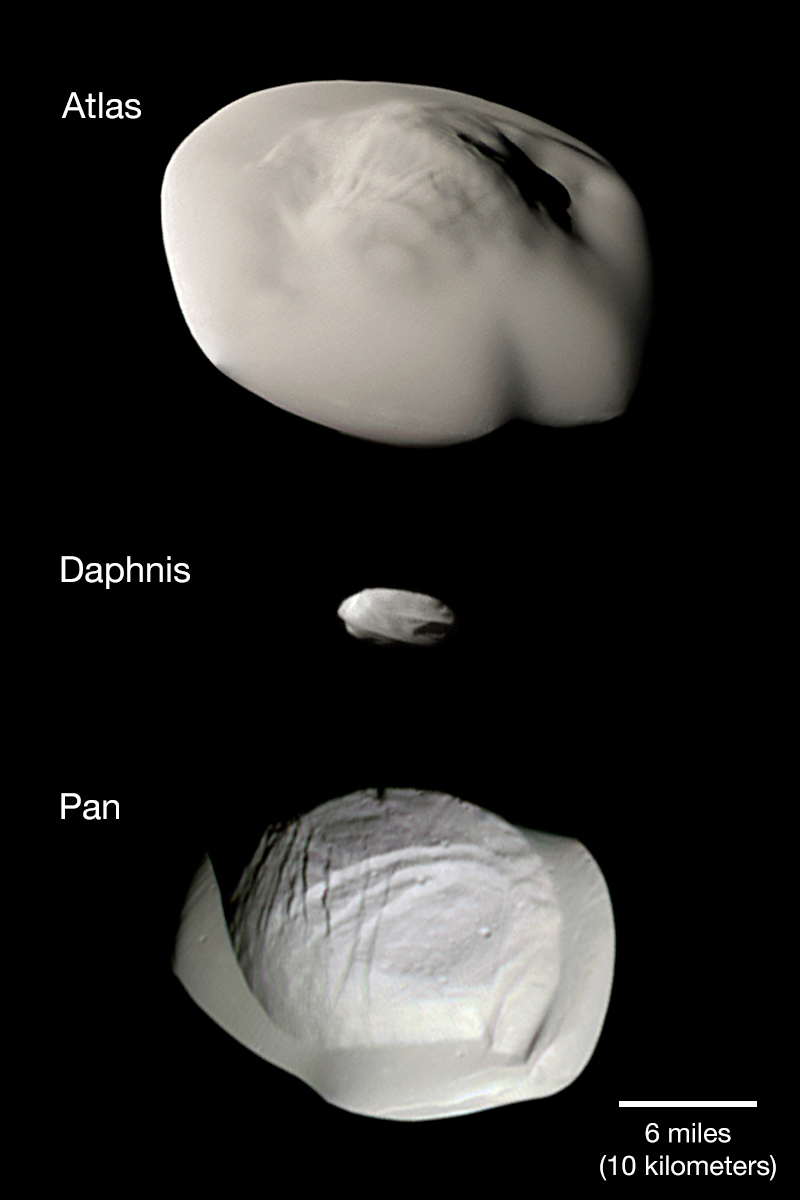

Atlas, Daphnis, and Pan are small, inner, ring moons of Saturn, shown at the same scale in this montage of images from the still Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft. In fact, Daphnis was discovered in Cassini images from 2005. Atlas and Pan were first sighted in images from the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. Flying saucer-shaped Atlas orbits near the outer edge of Saturn's bright A Ring while Daphnis orbits inside the A Ring's narrow Keeler Gap and Pan within the A Ring's larger Encke Gap. The curious equatorial ridges of the small ring moons could be built up by the accumulation of ring material over time. Even diminutive Daphnis makes waves in the ring material as it glides along the edge of the Keeler Gap.

Atlas, Daphnis, and Pan are small, inner, ring moons of Saturn, shown at the same scale in this montage of images from the still Saturn-orbiting Cassini spacecraft. In fact, Daphnis was discovered in Cassini images from 2005. Atlas and Pan were first sighted in images from the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft. Flying saucer-shaped Atlas orbits near the outer edge of Saturn's bright A Ring while Daphnis orbits inside the A Ring's narrow Keeler Gap and Pan within the A Ring's larger Encke Gap. The curious equatorial ridges of the small ring moons could be built up by the accumulation of ring material over time. Even diminutive Daphnis makes waves in the ring material as it glides along the edge of the Keeler Gap.ESA’s Mercury spacecraft has passed its final test in launch configuration, the last time it will be stacked like this before being reassembled at the launch site next year.